Writing Craft Book Reviews: A Book A Week

Fourth and last (for now!) in our series of book reviews featuring Kindle Unlimited books that explain ways to outline a novel. Let’s get ready for NaNoWriMo!

I'm an affiliate.

Some of the links on this page are affiliate links, but the opinions in my posts are my own, and I only mention products that I like and use myself. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. What that means is that if you click one of the links on my site and make a purchase, I might recieve compensation at no extra cost to you.

Think back to your language arts classes in high school. Do you remember using CUPS for editing? (Really, this should be proofreading instead of editing, but our teachers were working with the curriculum they had!) If you’re thinking, “CUPS? For editing? Wha—?” here’s a short explanation of how to use the acronym to proofread your writing.

Each letter stands for a different thing to check when you are proofreading:

C – Capitalization

U – Usage

P – Punctuation

S – Spelling

When you are first starting to use the CUPS checklist for proofreading, you make four passes through your writing, checking for issues with one of these things on each pass. As you get more practice proofreading, you can take fewer passes.

My next few posts will go over each of the letters in the CUPS editing strategy one by one.

Going over all of the rules for punctuation marks would take a whole book, not just a blog post, so we’re going to look at the general rules for only the most common marks. If you need to know what punctuation mark to use in a specific instance, I recommend The Grammar Girl podcast and blog here. Grammar Girl :: Quick and Dirty Tips ™

Let’s see how the rules for punctuation marks work in the ongoing saga of Aunt Maggie’s apartment. Here is the next section without any punctuation at all:

Maggies too small couch was so comfortable I drifted off for a bit hugging one of the pillows on the couch and daydreaming about the last time Id seen Aunt Maggie Suddenly I was dragged back to the present by a sound at the apartments door I was shocked when its handle started to turn I was sure that Id locked it when I came in

Excuse me I asked can I help you

The guy who opened the door looked even more surprised than I felt His eyebrows rose his forehead wrinkled and his jaw dropped

What are you doing in my apartment You cant come in here he yelped

I couldn’t believe the nerve of the guy, asking what I was doing here It’s not your apartment it’s my aunts apartment I replied firmly What are you doing here

Maggies gone for the summer and Im staying here I dont know how you got in but can you please leave my apartment He dropped a set of keys a paperback book and a phone on the counter and then stepped back holding open the door.

Pretty difficult to read, wasn’t it? Now compare that to the correctly punctuated section, here:

Maggie’s too-small couch was so comfortable! I drifted off for a bit, hugging one of the pillows on the couch and daydreaming about the last time I’d seen Aunt Maggie. Suddenly, I was dragged back to the present by a sound at the apartment’s door. I was shocked when its handle started to turn; I was sure that I’d locked it when I came in.

“Excuse me,” I asked, “can I help you?”

The guy who opened the door looked even more surprised than I felt: His eyebrows rose, his forehead wrinkled, and his jaw dropped.

“What are you doing in my apartment? You can’t come in here!” he yelped.

I couldn’t believe the nerve of the guy, asking what I was doing here! “It’s not your apartment; it’s my aunt’s apartment!” I replied firmly. “What are you doing here?”

“Maggie’s gone for the summer, and I’m staying here. I don’t know how you got in, but can you please leave my apartment.” He dropped a set of keys, a paperback book, and a phone on the counter and then stepped back, holding open the door.

I think that the second section is so much easier to read.

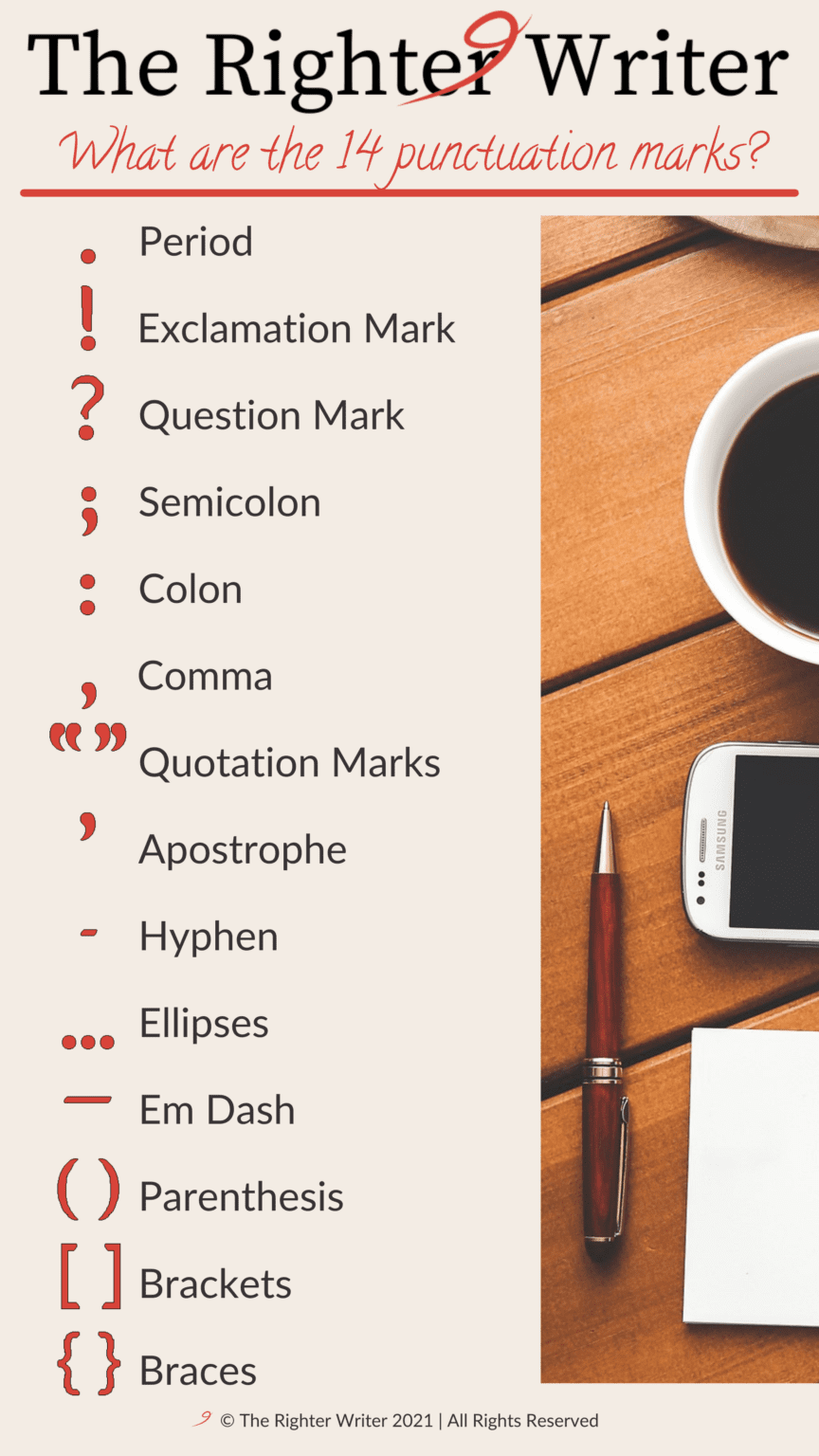

Did you even know that there were 14 different punctuation marks in English? They are:

A period is the last thing in a sentence and says to the reader that it is the end of one thought. The next sentence is going to start a new thought.

Maggie’s gone for the summer, and I’m staying here.

An exclamation point also ends a single idea, but it also tells the reader that this idea is important and has a lot of emotion behind it.

The couch was so comfortable! (She’s really happy here.)

It’s my aunt’s apartment! (Here, she’s upset.)

Watch out for adding more than one exclamation mark. It is probably fine in casual writing, but it stands out in business writing and can look unprofessional.

See you Friday! I’m so excited about the party!!!

I’ve definitely texted something like that before, but imagine that it said:

See you Friday! I’m really looking forward to the sales conference!!!

A question mark ends a sentence that is a question. (Right?)

What are you doing in my apartment?

One of the things to pay attention to with question marks is that some sentences look like questions but are actually something else.

This example is a rhetorical question—the man isn’t actually asking if Maggie’s niece is able to leave; he’s ordering her to leave—so you can put a period at the end or a question mark, it’s up to you and what style you like.

I don’t know how you got in, but can you please leave my apartment. (or a ?)

The next sentence is a reported question. She is just reporting what the man asked, not quoting exactly what he said. A question mark would be wrong here, but we could add an exclamation mark because this woman is pretty upset.

I couldn’t believe the nerve of the guy, asking what I was doing here!

Here’s an example of a common mistake with reported questions:

He asked what I was doing here?

There are two ways you can fix it. You can make it a quote, like this:

He asked, “What are you doing here?”

Or give it a period at the end, like this:

He asked what I was doing here.

You’ll probably see a semicolon connecting two related ideas, and they are probably complete sentences.

I was shocked when its handle started to turn; I was sure that I’d locked it when I came in.

You could also write this with a connection word.

I was shocked when its handle started to turn because I was sure that I’d locked it when I came in.

Or as two separate sentences with a period.

I was shocked when its handle started to turn. I was sure that I’d locked it when I came in.

Semicolons are also used with lists when the things you’ve listed have commas in them already.

I bought a blue, green, and white sweater; a pink, purple, and gold sweater; and a red, white, and blue sweater.

A colon can set off a list, too, especially if it is something that you really want the reader to pay attention to, like the list of punctuation marks in the heading of this section.

A colon draws attention to something important.

I think of the two dots as eyes that say, “Look here!”

We can compare that to the correctly punctuated section: (This colon says, “Look at this part coming up!”)

The guy who opened the door looked even more surprised than I felt: His eyebrows rose, his forehead wrinkled, and his jaw dropped. (Look at these! These are why he looked surprised!)

There have been long blog posts on just the rules of punctuation for commas, so I’m just giving you an overview of the places that you are most likely to use or see commas day-to-day.

The most common is probably lists.

He dropped a set of keys, a paperback book, and a phone on the counter and then stepped back, holding open the door.

His eyebrows rose, his forehead wrinkled, and his jaw dropped.

Please argue about the serial comma (also called the Oxford comma) someplace else. I like it, so I’m using it. You do what you like.

When two ideas have both a subject and a verb and are connected with a conjunction (and, but, for, or, nor, so, yet) you need a comma before the conjunction.

Maggie’s gone for the summer, and I’m staying here.

I don’t know how you got in, but can you please leave my apartment.

If one of the ideas doesn’t include both a subject and a verb—for instance when the subject is the same for both ideas—then you should not use a comma.

Maggie’s gone for the summer but will be back in September. Maggie is the subject for both verbs: gone and will be back.

I’m hugging one of the pillows on the couch and daydreaming about the last time I’d seen Aunt Maggie. I am doing both of the actions: hugging and daydreaming.

Commas set off information that you don’t need and could get rid of if you wanted. If the information has to be there to make the meaning clear, don’t use a comma.

My aunt who gave me my love of cooking was at the door. (No commas)

This means that I have many aunts, so, in order to know which aunt it is, you have to clarify that it’s the aunt who gave me my love of cooking.

My aunt, who gave me my love of cooking, was at the door.

In this case, I only have one aunt. Even without the extra information, it’s obvious which aunt it is because there’s only one choice.

Information that you don’t really need often comes at the beginning of the sentence,.

Unfortunately, Aunt Maggie is away for the summer.

As you can see, that sentence would be fine without the word unfortunately.

Whether you use a comma or not is also based on the order of the sentence. (Yeah, it drives me nuts, too, but I don’t make the rules…)

Because this is at the front of the sentence, we need to set it off with a comma.

This time it doesn’t need a comma because this phrase is at the end.

When a subordinate clause comes at the beginning of the sentence, it is set off with a comma.

It doesn’t need a comma when a subordinate clause comes at the end of the sentence.

(I try not to use jargon in these posts… You can think of a subordinate clause as something that sounds unfinished when you say it by itself. Like the phrase because this is a the front of the sentence can’t stand alone and make a sentence—it needs more.)

Commas can also be found in dates, places, and sentences that use the words yes or no.

Were you born in Portland, Oregon?

No, I wasn’t.

Were you at work on Friday, October 1, 2021?

Yes, I was.

There are so many times when whether or not to use a comma depends on the situation. In general, the trend lately has been to simplify as much as possible. If the sentence is clear without the comma, go ahead and leave it out. For cases when you’re not sure, you can look up the rule online or in a style guide. (Or you can always hire a proofreader—insert shameless plug here—to check your work for you.)

“Excuse me,” I asked, “can I help you?”

The most confusing part of using quotation marks is how they interact with the different punctuation marks in the sentence.

In the US, commas and periods always go inside the quotation marks. (The UK has different rules, which I’m not as familiar with, so I’m going to skip over those.) Exclamation marks and question marks sometimes go inside the quotation marks and sometimes outside. You need to see if the punctuation applies to the quote or to the whole sentence.

In this sentence, the quote itself is a question, so the question mark is inside the quotation marks.

“Excuse me,” I asked, “can I help you?”

Here, the whole sentence is a question, but the quote is a statement, so the question mark is outside the quotation marks.

Did he really say, “I’m living here”?

There are some times when people add quotation marks where they shouldn’t be.

Quotation marks are not for emphasis! That’s what bold is for. So don’t do this:

I was “shocked” when the handle started to turn…

Quotation marks are only for short things: short stories, songs, chapter titles, articles, and individual TV episodes. Titles of longer things go in italics. So this example is wrong:

I loved “Frozen.”

And this one is right:

“The Pancake Batter Anomaly” is my favorite episode of The Big Bang Theory because it has the song “Soft Kitty.”

Don’t use quotation marks with reported speech. They are only for the exact words that a person said, so this sentence doesn’t work:

She said “I can only stay at West Sunvale Terrace until my aunt returns in the fall.”

Either change the sentence into a quote of the exact words that she said, like this:

She said “You can only stay at West Sunvale Terrace until your aunt returns in the fall.”

Or just get rid of any quotation marks, like this:

She said I can only stay at West Sunvale Terrace until my aunt returns in the fall.

That is seven out of the 14 punctuation marks in English. We’re half-finished–well, we’re not actually going to cover all of them, so we’re probably more like two-thirds finished.

Up until now, the different punctuation marks served to break up sentences into ideas so they were easier to understand.

An apostrophe has two main jobs: to make contractions and to make possessives.

Contractions have some letters taken out and replaced with an apostrophe. We do this a lot with the verbs to be and to have.

I am

you are

he is

she is

it is

we are

they are

Maggie’s gone for the summer, and I’m staying here.

I have

you have

he has

she has

it has

we have

they have

I’ve never been here before, but he’s come here every summer.

There are also a lot of contractions of the word not.

isn’t

can’t

won’t

haven’t

shouldn’t

couldn’t

didn’t

You can’t come in here!

When you use an apostrophe to make nouns possessive, you are saying that something owns something else or the things are linked.

My mother’s sister is my aunt.

It’s my aunt’s apartment!

Maggie’s too-small couch was so comfortable!

The kitchen’s floor was gold.

Apostrophes don’t make a word plural! If there is more than one of something, just add the letter s and you’re set.

He dropped a set of keys… (NOT key’s)

His eyebrows rose… (NOT eyebrow’s)

Some words always have hyphens, some words never have hyphens, and some words sometimes have hyphens. And isn’t that as clear as mud! (Did you notice the reflexive question with no question mark?)

Words that always have hyphens are things like these: mother-in-law, large-scale, or good-looking.

The style guide that I usually use (Chicago Manual of Style) says to hyphenate numbers below 100: ninety-nine, two-thirds, 16-ounce. You can also hyphenate numbers when they’re part of a descriptive word like these: half-finished, half-baked, half-thought.

If the word begins with the prefix self-, all-, or ex, then it most likely needs a hyphen:

My ex-boss looks self-satisfied because he feels all-powerful in the office.

On the other hand, adverbs (think of words that end in -ly) never get hyphenated. So you shouldn’t write about a really-comfortable couch or a relatively-small apartment.

The tricky bit is when words sometimes need a hyphen and sometimes don’t.

Some words mean different things when they have hyphens, like re-creation and recreation or mid-section and midsection.

Some words get hyphens depending on where they are in the sentence. A compound word before a noun is easier to understand when it’s hyphenated, so that’s the general rule.

That is a one-person apartment.

Maggie’s too-small couch was so comfortable!

The same word doesn’t need a hyphen when it’s after the noun because the meaning is clear.

The apartment was for one person.

Maggie’s couch was too small.

These punctuation marks aren’t used as much as the others, so you probably won’t see them very often in everyday writing like emails or blog posts. I did use some of them in this post, though; if you felt like it, you could go through and see what you can find.

ellipsis

em dash

parentheses

brackets

braces

There are so many rules for punctuation that it is hard to remember them all. Keep in mind that the reason we use all these different punctuation marks is that they make our writing easier to read and understand. In general, if they don’t help a reader to follow your thought, don’t bother with them!

If you’re still unsure about what rule to follow in your particular case, I would google something specific, like “is there a comma after because?” Or check out an online style guide, like the Chicago Manual of Style or the MLA Style Center. And, of course, you can hire a proofreader to catch the last mistakes that slipped by.

If you want more practice proofreading your own writing, check out my other posts on using the CUPS strategy for editing: capitalization, usage, and spelling.

I help authors, researchers, business people, students, and web marketers to polish their writing before they send it out into the world.

Fourth and last (for now!) in our series of book reviews featuring Kindle Unlimited books that explain ways to outline a novel. Let’s get ready for NaNoWriMo!

Third in our series of book reviews featuring Kindle Unlimited books that explain ways to outline a novel. Let’s get ready for NaNoWriMo!

Second in our series of book reviews featuring Kindle Unlimited books that explain ways to outline a novel. Let’s get ready for NaNoWriMo!

3 Responses

Very informative